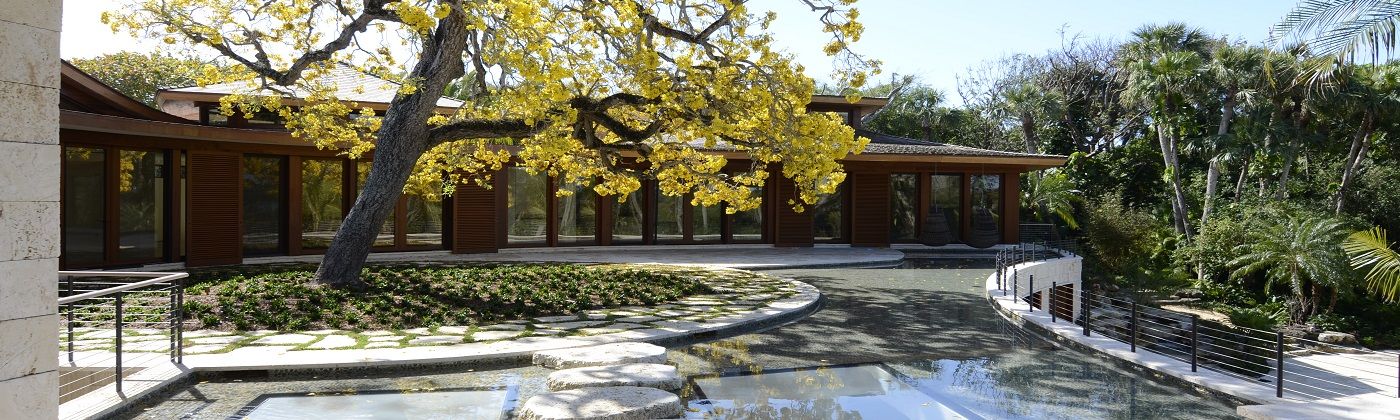

Landscape Design & Architecture

A well-designed and built landscape starts with highly trained, experienced, and certified landscape designers with years of experience and the knowledge, creative skills and commitment to take on even the toughest landscape situations.

Landscape Design

In South Florida, landscape design can be challenging. Plant selection, fertilization, water conservation and control of invasive plants and weeds make our area one of the most specialized areas in the country for successful landscaping.

Jenkins Landscape Designers

Our knowledgeable designers can identify and select plants, use proper design principles, sketch design ideas for customers, suggest plants and irrigation systems and work on large design projects.

The Landscape Design Process

Our landscape design projects begin with a Planting Design Plan that informs our clients, crews, and estimators. A project may involve the re-defining of shrub beds, development of screen planting, perennial bed plantings, or a major overhaul of an existing landscape. The Planting Design Plan is at the center of communication with our landscape designer, the client and our crew leaders, and it defines our itemized proposal.

Landscape Architecture

Jenkins contracts with Landscape Architects that are a good match for specific projects, and offers recommendations to any homeowner or commercial entity seeking a reputable and reliable Landscape Architect. These landscape professionals have a college degree and are licensed by the state of Florida to design hardscapes (walkways, walls, driveways) and softscapes (areas of plant material), often in collaboration with building architects, surveyors, engineers, and others. Determining when you need a landscape architect can be difficult, and if you are unsure you can always consult with Jenkins to get our opinion.

Jenkins Landscape Co.

12260 SE Dixie Hwy

Hobe Sound, FL 33455

Main Office: (772) 546-2861